As part of Kaspersky’s Bring on the Future series, we meet businesses around the world who are changing their industry and society for the better.

The seaside. For some, a place of rest, relaxation, and perhaps a hint of volleyball. But, to Eric Matzner, CEO of Project Vesta, beaches, and more importantly, olivine rocks, could hold the solution to our climate change battle. I spoke to Eric about Project Vesta’s mission, the Paris Agreement, and how a little-known rock could pull trillions of tons of carbon from our atmosphere.

Ryan Loftus: So what’s the story behind Project Vesta, Eric?

Eric Matzner: Project Vesta was born out of my climate angst, to be honest. It started when I was looking through various climate agreements, like the Paris Agreement. The secret, hidden in plain sight, is that even with these proposals and the suggested cuts, to keep global warming below 1.5C by the end of the century, we need to remove between 100m to a trillion tons of CO2.

Large-scale carbon removal is imperative. I started thinking about different technologies that could do the job, but nearly all of the suggested techniques have challenges, such as limitations on scale, requiring a lot of energy or competing for land use.

Then I came across a paper called Rolling Stones, which focused on a scalable way detailing how olivine rock can capture CO2 economically to mitigate global warming, while also combating ocean acidification. The basic idea was that olivine rock, placed on shell beaches, could help remove total human carbon emissions.

Other research shows that olivine rock weathering could scale up easily, wasn’t too energy-intensive and didn’t compete for arable land. I searched far and wide to find the current status of the technique to see if there was a pilot project, emailing scientists and asking people in the industry but found that no one was doing it. So after researching it, I decided that if this were to become a reality, I would need to create the project. So, I started Project Vesta, formed a team, and launched on Earth Day 2019.

It’s ambitious! What’s the big vision?

At its peak, I hope Project Vesta can galvanize the world into removing large quantities of CO2, by providing irreversible, permanent storage of CO2 at an economically viable price, that doesn’t compete for farmland or other resources.

Exactly what the world needs right now. How does the process work?

There are reserves of a rock called olivine, all over the world, for which there is almost no demand. Project Vesta wants to mine these rocks from quarries on the surface and then place them on high-energy beaches in tropical areas.

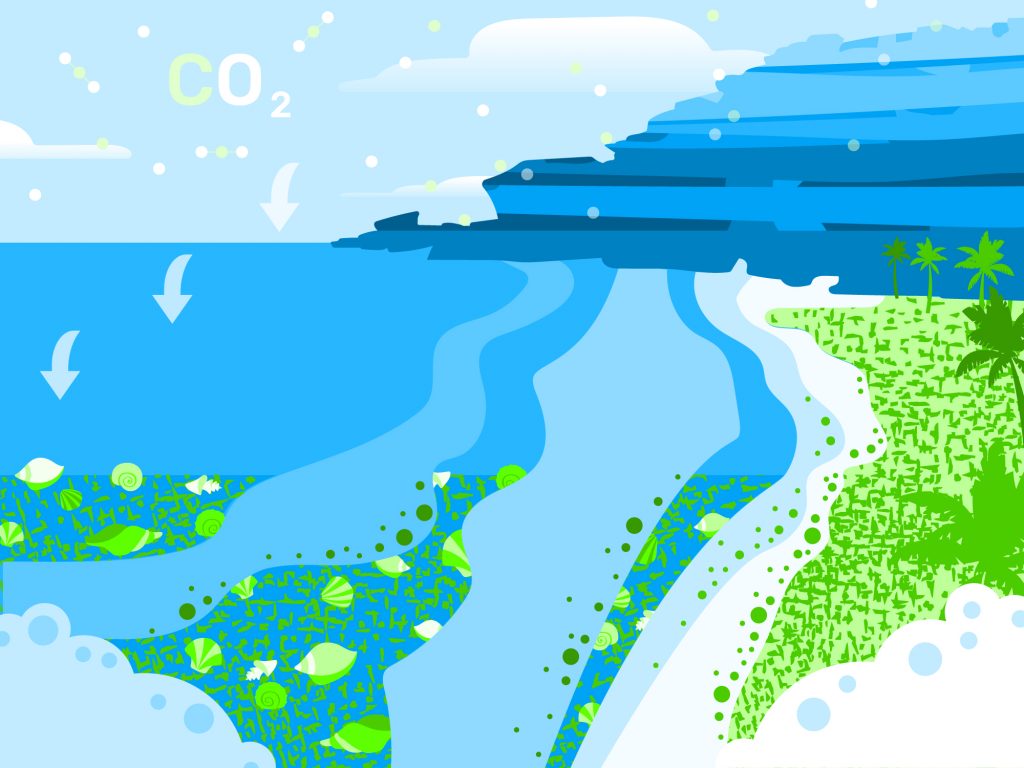

This is part of Earth’s natural carbonate-silicate cycle: rain mixes with CO2 to create carbonic acid, which falls on rocks, weathering them down and transporting water (filled with ions) into rivers, which eventually ends up in the ocean. Over time, usually millions of years, the carbonic acid becomes bicarbonate and then calcium carbonate, which corals and other marine animals use to build shells. When they die and fall to the seafloor, the shells turn into sediments and then form limestone, trapping CO2 for millions of years.

By adding olivine directly to the ocean, we dramatically speed up the carbon removal process, by cutting out these steps in the middle. The bicarbonate molecule is alkaline, as opposed to the acidic CO2 dissolved in water, so we can help create this molecule, which raises the PH of the ocean, helping to de-acidify it. In turn, other parts of the rock are inert or not available to organisms, and are not predicted to have any adverse effects.

The reason we use beaches is to make the process efficient; otherwise, we would use too much energy to grind the rocks down to very fine particles. This is how it works: reserves of olivine near coastal areas are located and then harvested; the rock is then lightly crushed to pebble-sized grains and placed onto beaches where the wave motion tumbles them and grinds them down. The process also removes a coating on the surface that would typically slow the reaction.

That’s some process. How will you do that?

Right now, we’re looking for states and cities with access and legal ownership over beaches to help provide a testbed for our pilot safety study. We need two bays nearby each other, one as control and one in which to put olivine rocks. Then we’ll measure the results.

Once we have our pilot project, we’ll write a research paper summarising all of the existing literature on coastal weathering, including our results and findings, to demonstrate the viability of our process and take it to policymakers.

What are the benefits of fighting climate change this way?

This is a method of carbon removal that Earth uses to put 99.9 percent of its carbon into rock. We know the process works and can scale to the trillion-ton level that we need to have a chance to stop catastrophic global warming. By using undeveloped coastlines with otherwise unwanted resources, we can scale this project to global levels without disrupting food systems or other limited resources in a world with a growing population. This is a solution that’s permanent, scalable and can be done with today’s technology. We could reach an operational price of below ten dollars for each tonne of CO2 removed.

And there are co-benefits too. Olivine is made up, in part, by magnesium and silica. The latter, when released through weathering, becomes shells for diatoms – microalgae found in oceans, comprising a hugely important part of the food chain – which is threatened by ocean acidification. Our project might be worthwhile just for the acidification effects. A recent study reported that Dungeness Crab’s shells are dissolving much sooner than predicted due to pockets of ocean acidity, so that lends extra importance to our work. Another benefit of this method – if the world gets hotter and the oceans more acidic, our weathering process will speed up, making it future proof.

Two-pronged benefits then. How do you differ from other companies doing the same?

I don’t know of anyone else doing this, beyond the scientists we’re working with across the world. But if there is, we’d love to collaborate. We’re a non-profit on a mission to solve humanity’s biggest challenge, and we’re always looking for partners and friends in the industry.

In terms of the security of your project, how do you keep your customer and technology data secure?

For our donors, we use a tokenization system through Stripe, where we do not even possess credit card information. We don’t have a vast amount of proprietary data, but we limit access strictly to the key decision-makers. We’re an open-source non-profit, so as we generate scientific data, we’ll publish that openly.

Good practice. What significant challenges have you faced so far?

Trying to bring together scientists who have been working on different elements of this concept for years, then uniting them across different time-zones, dialects, regions and fields!

On the flip side, what big successes have you had?

Well, to date, we’ve raised over $100,000 for our pilot project. We’ve had great feedback about how elegant our solution is. We’re giving people hope because they see this could be a significant part of the solution to climate change. And we have key scientists in the field on board working on a paper about olivine weathering.

Well said. What does the future hold for Project Vesta?

We need to raise $1.5M to deploy our two pilot projects and monitor them for two years. So, we’re fundraising, crowdfunding and selling our line of olivine jewelry to raise money. Right now, the money is helping fund our operations and spread awareness. Once we have two beaches for our pilot project, the funds raised from the jewelry will correlate to an amount of olivine we will place on a beach. Eventually, we’ll make peridot gemstone rings – olivine is also known as peridot, the august birthstone, in its crystal form – which we hope will replace the role of diamonds in our society.

We aspire to shift society’s value from the past compression of carbon (which is how a diamond is formed) to the future removal of carbon (which is how the “profit” from the ring will be used). We hope the jewelry will connect people to their carbon removal, giving them something tangible and symbolic, as opposed to just a donation. Right now, we’re selling a necklace called the Grain of Hope, which is a single grain of olivine suspended in a sand timer vial, a metaphor to demonstrate that olivine has the potential to stop time from running out on us to combat this most pressing of human issues.

Soon you’ll be able to subscribe to Project Vesta for $25 a year, which will place one ton of olivine rock onto a beach for you – almost removing your yearly CO2 emissions per year. Project Vesta wants to prove the viability of olivine weathering for CO2 removal. In turn, de-risking the process and making it an easy choice for policymakers, who can then, we hope, action it to help save our planet.