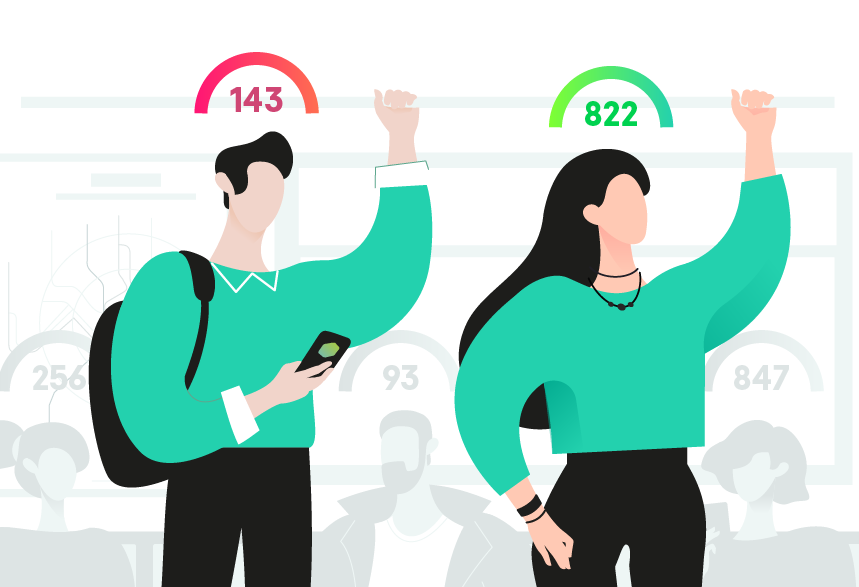

Imagine: every action you take, every interaction you have, every movement you make—all reduced to a single rating on a five-point scale. A higher rating opens the door to fabulous opportunities and special benefits, while a low rating can, essentially, keep you shut off from the rest of society. That is, in essence (albeit simplified), what a social rating or social scoring system is.

One of the most famous social credit systems is the one proposed by the Chinese government. However, it is not the only entity that is imposing social monitoring solutions. In January, the UK government revealed that they would be using live facial recognition software on the streets of London in order to find suspects wanted by the police and similar systems are already used by law enforcement agencies and government organizations around the world. Multiple other entities, such as various insurance companies around the world, have announced or deployed systems that would allow its operators to effectively gather information about people’s behavior for use in important decisions. For example, life insurers in New York are allowed to make decisions about their clients using information found in social networks. The car insurance industry utilizes solutions that calculate the resulting fees charged based on information received from a tracking device deliberately installed in a car.

There are solutions allowing owners of organizations, like restaurants, to create black lists of people not allowed to enter a bar or a restaurant due to previous misbehavior.

Sharing economy services, like Airbnb, taxi or delivery services all have some kind of scoring system that evaluates those that participate in the service from various points of view.

With the 2020 Covid-19 pandemic, questions related to citizen monitoring have been raised repeatedly, and regulators worldwide have proposed various solutions to track citizens for the sake of stopping the disease.

In Israel, a special app was launched that allows users to check if their whereabouts match those of someone who has previously been infected. Other governments are also using surveillance technology to track the spread of the disease.

As in the case of Covid-19, there is a logical reason behind every other system that tracks human behavior and makes decisions based on the results of its analysis: no one wants to get infected because someone else decided not to keep themselves in self isolation, no one wants to find themselves in a ride with a rude driver or passenger, and no one wants to discover that their recently rented apartment comes with anti-social neighbors. Moreover, in an ideal society socially responsible behavior should be rewarded because it makes the society better and safer in general.

Yet, the very old questions of how much surveillance is too much surveillance and what is the price paid for everybody’s wellbeing inevitably arise. And so does another extremely important question: who watches the watcher?

What we know so far:

The premise behind a nationwide social rating system itself is relatively simple: every citizen receives a certain score to start, and certain actions either lower or increase your score. For example, donating to charity would increase your score, while buying cigarettes would lower it. People can then either be rewarded or punished based on their rating. The government, for example, could restrict a person’s travel, prevent them from entering the best universities, or even take their dog away if their score drops low enough.

Two of the biggest unanswered questions are what the system will actually look like in practice and how the system operates from a technological standpoint. There are several possible reasons for this.

First, the developers of the system understand that the more they reveal about the system, the more they open it up to vulnerabilities (more on that later).

Second, it’s entirely possible that the creators themselves do not fully understand how this system works. Many rating systems used today are built on large volumes of historical data and machine learning models that predict the future behavior and successes of system participants. For example, Microsoft uses such models to rank the skill level of players in online games, banks evaluate the reliability of potential borrowers when they submit applications for loans, and several companies have even tried to automate the process of reviewing resumes for open vacancies. In these situations, developers put their trust in the algorithms.

In Europe and America, legislation is actively being developed that makes it obligatory for companies to present people with understandable information about why their rating has declined or increased (ECOA 1974, GDPR 2016)—i.e. so that automation doesn’t become black box testing (the tester knows what the software is supposed to do but not how). However, the same is not happening in every other country that is considering the implementation of a social scoring system in the future, at least based on the information we were able to find in public sources. If true, that means a host of decisions can be placed entirely in the hands of AI, which is a problem.

AI is based on machine learning algorithms, which, despite being generally lauded by the technological industry as a “cure-all”, are far from perfect. Like any other computer system, they can be prone to errors. For example, in cybersecurity, machine-learning algorithms are used to rapidly detect previously unknown malware. However, there is a problem: the higher the detection rate, the higher the chance you’ll run into “false positives“—i.e., the system determines a non-malicious file is malicious. This happens due to the very nature of how machine learning works: the ML-based system doesn’t look into the details of an object but compares the way it “looks” to other known objects. In some cases, “clean” objects may “look” a lot like malicious ones and a system that makes decisions based on scoring would most likely confirm the object as a malicious one. When applied to a world where people’s behavior is evaluated by a fully automated system, this particularity of machine learning systems may lead to multiple unpleasant situations where an innocent person is confirmed as the one behind “wrong” actions.

These systems are also susceptible to issues such as developer bias, false correlations, and feedback loops, and, unless specifically included by the developer, the algorithms do not factor in ethical considerations. To simply input massive quantities of information into a machine learning system and then accept the result without any critical assessment could lead to a host of unintended consequences, including choices that ultimately infringe upon the rights of certain citizens.

Lastly, should the control over a particular system be concentrated in the hands of only one social group, their ability to change the rules of how the system works may significantly influence the life of those social groups who are not in a position to influence the scoring rules.

A System Ripe for Manipulation

From a technical standpoint, the way the social credit system is designed leaves it particularly vulnerable to artificial manipulations, such as lowering someone’s score for various purposes.

Based on publicly available information about social credit systems, most of them are built on top of a publically available interfaces, which contains massive amounts of personal data, including all “offenses” committed. This type of interface is more prone to leaks, and, if accessed illegally, could lead to terrible consequences for the individuals attacked. It also doesn’t have to be hacked. Entities that use such systems often provide APIs that allow people to look up the various violations of an individual by inputting information like his or her phone number or passport number.

In fact, the openness of such systems could be exactly why entities that use them have chosen this type of interface. In certain countries, public censure is the basis for many types of punishments: photographs of traffic violators are posted to billboards, for example. In other words, their goal is often to make private information publicly—or at the very least easily—accessible. But this can easily give rise to issues like fraud and bullying.

Vulnerabilities within the System

But such social credit score systems aren’t just vulnerable because they may use a public interface. They are a computer system and, like any other computer system, they are susceptible to attacks. These can be divided into three groups:

-

Attacks on the technical implementation.

A countrywide control over the actions and movements of every citizen (a requirement for nationwide social scoring systems to be efficient) mandates coordination between a massive number of various types of sensors and tracking devices, all united under the term Internet of Things (IoT). IoT is essentially a group of devices connected to a network that can collect and transfer data automatically. Think about apps that let you unlock your doors from your cell phone or the sensors in printers that tell you the ink is low. Even heart implants are “smart devices”. And any time you connect a device to the internet, you immediately increase the security risks. Why? Because a device connected to the internet can be hacked. IoT devices are particularly vulnerable because of how rapidly they’re developed and the fact that there is a lack of overarching security standards. In the first half of 2019, Kaspersky experts uncovered 105 million attacks on IoT devices. And the more IoT devices connected, the greater the attack surface, meaning a system as massive as the one required for a single social credit system for more than one billion people is just waiting to be attacked.

-

Attacks on the programming implementation.

Apart from the standard software vulnerabilities found in any distributed digital system, the machine learning-based scoring mechanism carries an additional risk for attacks against its algorithms. A large portion of the tasks in the social credit system requires the use of speech and facial recognition algorithms, as well as an automatic analysis of large volumes of text information (for example, posts on social media) or other similar social network structures. This is accomplished with neural networks based on current methods of deep learning, which are highly vulnerable. For one, they’re surprisingly easy to trick. In 2016, researchers were able to trick a facial recognition system into misinterpreting their identity by wearing patterned glasses with frames that contained hallucinogenic print—a type of potential attack dubbed by experts as “adversarial machine learning”.

The assumption is that there would be an attacker attempting to fool the system for personal benefit or malicious purposes, instead of just playing a fun game of mistaken identity. Think tricking a self-driving car into speeding through stop signs. Or, you could purchase a special t-shirt with various license plates numbers that would trigger Automatic License Plate Readers. Should you jaywalk or park illegally, the security cameras would register the license plate numbers on the shirt as the violators, leading to fines being issued to dozens of unsuspecting car owners. With a social rating system like those based on open access to data about citizens, anyone could manipulate the scores of their fellow citizen, say, by wearing special makeup while violating pedestrian traffic rules to trick the system into thinking they’re someone else and subsequently lowering the score of the targeted person.

-

Attacks on the system mechanics.

There is another type of vulnerability that doesn’t rest with the system’s technology or code: a vulnerability in the desired outcomes. In other words, the rules for certain actions could lead to entirely unexpected—and undesirable—results. For example, some of the current social scoring systems include lowering the rating of those who purchase “bad items” (cigarettes, alcohol, etc.) as a way to motivate their citizens to take better care of their health. However, this could lead to the emergence of a new type of black-market where those with extremely high ratings can resell “bad items” to citizens who are in danger of falling into an “undesirable zone”. On the other hand, those with money who wish to turn a profit by selling these “bad items” or simply want to inflate their ratings to receive a coveted job, can simply donate to charity, or even certain political organizations. As a result, a social rating becomes a second currency where, by manipulating the mechanisms used for establishing the rating, your score can be converted into real money and vice versa.

The consequences of a social scoring system that can determine your future while being simultaneously easy to manipulate and vulnerable to attacks are hard to predict—but potentially dangerous.

What would a society with a social ranking look like?

The basic idea behind a nationwide social credit system is that everything from people’s ability to use public transportation to the future job they can receive is based on a single score. In doing so, the score becomes the entire basis for a person’s societal standing. The likely outcome then will be a strengthening of social stratification. In fact, the social ranking system will directly affect the three aspects that, according to well-known sociologist Max Weber, form the basis of social stratification: wealth, power, and prestige.

- Wealth: a person born to parents with a low social rating most likely will not have the opportunity to enter a good, paid school or university. As a result, this person has a much smaller chance of receiving a quality education and finding a good, paid position, thereby severely restricting future income. On the other hand, a person in good standing will have access to the best jobs, meaning that he or she can always maintain a high rating by donating to charity.

- Power: a citizen with a low rating will potentially not be able to occupy a management position in state or commercial structures. As a result, power continues to stay with those who first built the ranking system and determined the rules for calculating the scores.

- Prestige: public censure is one of the main instruments used by the operators of currently existing social scoring systems to maintain control. Information about “undesirable citizens” located nearby will be posted in the public domain, and people who are not considered “undesirable” but communicate with such people will most likely receive a decrease in their own rating. As a result, people with low ratings will become outcasts without the opportunity to improve their position. Prestige will stay with those who were either born or purchased their way into the top of the rankings.

As the years progress, the gap between those with high ratings and those with low ratings will, presumably, widen, leading to a severely stratified society. Those who start at the bottom will most likely remain trapped there. We’ve all seen it in a famous episode of Black Mirror: a fictional world where people are fully dependent on their score. Released in 2016, the episode looks like a satirical science fiction story—until you realize that, practically all examples presented are modeled after real life.

Is a single rating system even possible?

Based on publicly available information, all currently operating systems don’t actually involve the existence of any kind of unified scale, as previously proposed. In reality, current ratings are collections of independent ratings that exist across a wide array of areas and organizations. Moreover, punishments are, as a rule, connected with the area (industry) in which the citizen committed the offense. For example, those who were fined for traveling on a train without a ticket receive limits on their use of public transportation. Or, if a person was blacklisted on one social network or an apartment rental service, they most likely will not experience similar issues in competing services. The overlap between different sectors is, so far, minimal.

Right now, we only see reviews for a taxi driver that are connected with the application through which we are making the order. If you order a car via Gett, you don’t see how many stars Uber users gave the driver. We also don’t know any additional information, such as how often the driver has been involved in car accidents outside working hours or how many times over the past month they’ve drunk alcohol. The nationwide system would, in theory, compile all of that data in one place. To do so, they must rely on the technologies adopted by leading national IT companies for the collection and processing of big data. This creates an environment in which the exchange of information about clients between different companies becomes much easier to implement, both from a technical and legal side.

In fact, such an exchange of information between different companies was launched long ago, although the scale is not yet so obvious. Many companies sell data about their users or offer services that help third-party companies learn something new about their clients without an explicit data transfer (sets of tags for targeted ads, services like AI-as-a-Service, collaboration between retail sites). Of course, this raises its own set of ethical questions, such as companies collecting data about their clients’ activity online, without their knowledge, and selling the information to the highest bidder.

In the future, what this process of exchanging and distributing personal data will look like depends on the politics of the state and its technological readiness. It’s entirely possible that in the near future, at least some governments will be able to implement the kind of unified social credit score that would account for every aspect of a person’s life.

Moving Forward:

The question, then, still remains: Will our reality, as a whole, devolve into a sort of dystopian future, a world where people have a smile perpetually plastered on their face in the hopes of picking up a few extra points and where those with low ratings are relegated to the outskirts of society? Probably not—at least not yet. There’s still far too many unknowns, and whether nationwide systems could actually be implemented in countries with such vastly different forms of government and legislative frameworks is unclear. Yet one thing is clear: as technology develops at an unhindered pace, the lines between digital tech and larger social and political issues will only become more blurred. When it comes to the proposed social rating system, the fundamental issue is one that the larger world of technology is already being forced to confront: the issue of privacy. After all, the social rating system only works if it’s able to collect vast amounts of personal data. How companies and societies will handle this increasingly pressing issue remains to be seen—no doubt, the approaches will be different.

As a security community, we have to pay attention and invest our resources in figuring out how citizens, government, and the private sector can navigate developing social scoring systems without sacrificing privacy, public safety, and commercial interests. At this moment, there is no right answer, and for that very reason, it’s difficult to advise people on how to specifically protect themselves from the negative effects of implementing social scoring systems. The solution should lie somewhere at the intersection of privacy protection technologies, government regulations, business practices and ethical principles—but all of these areas, as far as they relate to rating systems, have yet to be defined. Right now, we can only advise people living their digital lives to keep in mind that there are multiple scoring systems all around them that collect and analyze their information.

The good news is, while you can’t hide from surveillance or stamp out your digital footprint in its entirety, there are ways you can limit the type and amount of information about yourself that’s shared. Here are some steps you can take to better protect your privacy.

Here’s what you can do, according to Kaspersky experts:

- Change your privacy settings based on the level of protection you want on all the major social networking sites you use

- Be careful about what you post—not every photo needs to be online

- Block the installation of programs from unknown sources in your smartphone’s settings

- Pay attention to what permissions apps requests and turn off accessibility services

- Delete accounts, apps, and programs you no longer use, as they may still be collecting and processing information about you

- Use a VPN when logged onto unsecured, public WiFi

- Use a reliable security solution like Kaspersky Security Cloud that includes a Private Browsing feature, which prevents websites from collecting information about your activity online