Mac OS X Yosemite (10.10) has arrived, and it’s time to look at what it’s going to offer us from the security point of view. Apple has actually set up a special page dedicated to security for Mac OS X with lengthy text – there’s a lot of it, but it’s comprehensible and rather easy to read. However, it doesn’t say a lot about what features are new.

First of all, Apple states, security was “the first thought. Not an afterthought”. This is something extremely welcomed these days. Actually, it always has been but not every developer has been thinking about building in security from the ground up. Apple does it right, or at least it says it does.

Most of the security tools involved have a specific name – Gatekeeper, FileVault. It’s a marketing approach but it also helps to explain which does what.

#Security features in #Mac OS X Yosemite

Tweet

So, let’s look at them.

Gatekeeper

It’s an old (presented in Mac OS X Mountain Lion 10.8) feature protecting Mac from malware and “misbehaving apps downloaded from the internet”.

It’s similar in its purpose and behavior to the Windows User Account Control (UAC). In a nutshell, Gatekeeper checks whether the app downloaded from other places rather than Mac App Store has the proper Developer ID. If it does not, it won’t launch, unless setting are changed.

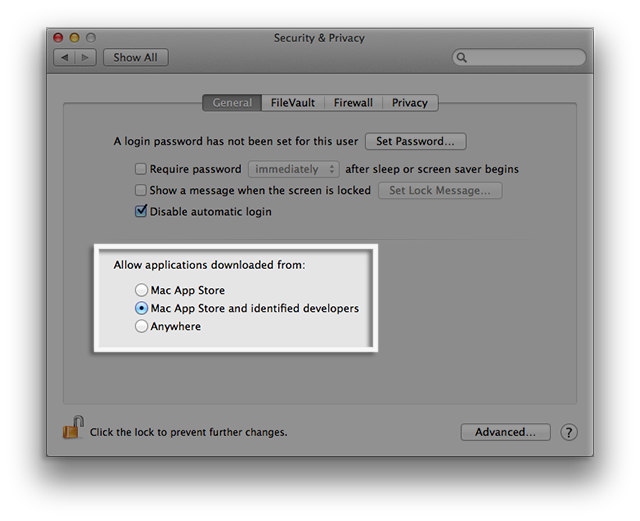

By default (unlike OS X Lion v10.7.5, for instance) Gatekeeper allows users to download apps from the Mac App Store and those signed with a Developer ID. Otherwise it’s blocked, but manual override is possible.

Other options include “Anywhere” (the least safe) and “Mac App Store” (nothing else; it’s the high security setting).

FileVault 2

Yet another security tool, it encrypts the entire drive on Mac, protecting the data with XTS-AES 128 encryption. Apple says that initial encryption is fast and unobtrusive. It can also encrypt any removable drive, helping the user secure Time Machine backups or other external drives.

FileVault 2 also allows users to wipe all the data on the drive, and it’s done in two stages. First, it kills the encryption keys from the Mac, which is supposed to make the data “completely inaccessible”, according to Apple. Then it proceeds with a thorough wipe of all data from the disk. So those who would like to recover anything from that drive will have a lot of “fun”. As a way to secure the sensitive data from getting into the wrong hands, it’s extremely useful. As is…

Remote Wipe

This allows users to delete all your personal data and restore your Mac to its factory settings, if it has “changed the owner” without your consent. The milder option is to set a passcode lock remotely.

iCloud.com and Find My iPhone app on iOS devices allow users to locate their missing Mac on a map. And if it is offline, as soon as it makes a Wi-Fi connection you’ll get a message. There is also an option to display a message on the screen with information about how to return the missing computer.

Passwords

The Safari Browser is equipped with Password Generator that creates strong passwords for your online accounts.

There’s also iCloud Keychain that stores your logins and passwords (as well as your credit card information) with 256-bit AES encryption. iCloud also allows users to sync all usernames and passwords between Apple-produced devices – Mac, iPhone, iPad and iPod touch.

This autofill has just one setback: if someone unfriendly gets a chance to use your Mac in your absence, it may have ramifications. So it is strongly recommended that users apply the Disable Automatic Login in their Security & Privacy settings.

Privacy controls

These options allow (or disallow) certain apps to request your location data, with an explanation on how Location Services may interfere with privacy.

There are also certain “Accessibility” tabs, which allow users to permit certain apps to “control your computer” (an obvious counterpart to Windows – some applications, especially legacy ones, request a “Run as an Administrator” setting to get going). It’s up to a user to decide what apps will have these privileges. While it is not necessary affecting privacy on its own, as an extra security feature it is definitely worth mentioning.

Actually Apple could have done more with privacy: it appears that Spotlight on Yosemite by default reports user’s current location (at the city level) and all their search queries to Apple and third parties. To get rid of it, Spotlight Suggestions and Bing Web Searches should be disabled in System Preferences > Spotlight > Search Results. Spotlight Suggestions also require disabling separately in Safari settings.

Antiphishing

The tool (actually introduced quite some time ago) is in place. An increasingly common problem, phishing requires special countermeasures, and it’s a good thing that Apple gives them.

Firewall

It’s a basic tool that allows users to accept or deny incoming connections to your Mac by application.

It does not, however, provide outbound firewall protection, so it would be reasonable to install something more robust.

Apple shows the right direction for improving #security of Mac OS X.

Tweet

Sandboxing and Core-level Protection

Here we have App Sandbox, a feature introduced in Mac OS X Lion 10.7; an isolated environment for the apps that may turn harmful to the system. Interestingly, OS X delivers sandboxing protection in Safari by sandboxing the built-in PDF viewer and plug-ins such as Adobe Flash Player, Silverlight, QuickTime, and Oracle Java – exactly the software that is among the most vulnerable and exploited.

But also OS X sandboxes apps like the Mac App Store, Messages, Calendar, Contacts, Dictionary, Font Book, Photo Booth, Quick Look Previews, Notes, Reminders, Game Center, Mail, and FaceTime, so that nothing potentially malicious creeps in.

Here we also have run time protection at the core level: built into the processor XD (execute disable) feature that “creates a strong wall between memory used for data and memory used for executable instructions”. According to Apple’s description, this protects against malware that attempts to trick the Mac into treating data the same way it treats a program in order to compromise your system.

Also Address Space Layout Randomization (ASLR) is used both for the memory used by the kernel, randomly arranging the positions of key data areas of every program. This technique protects from certain attacks (such as buffer overflow) by making it more difficult for an attacker to predict target addresses.

Apple introduced randomization for system libraries with Mac OS X Leopard 10.5, and expanded it to the entire system with Mountain Lion 10.8 in July 2012. So it is there for the time being.

Judging by the features listed above Apple made an effort to make Mac OS X secure, and apparently will keep doing so. It shows Apple is moving in the right direction by addressing cybersecurity problems and diminishing the possible attack surface by various means and tools, both basic and advanced.

It doesn’t, however, mean that it is an “absolutely” protected operating system – there are no such systems , unfortunately. Moreover, the number of threats targeting Mac OS X, specifically, is growing as does the number of Mac users. This certainly has drawn the attention of criminals, who are looking into vulnerabilities and occasionally finding them.

macOS

macOS

Tips

Tips